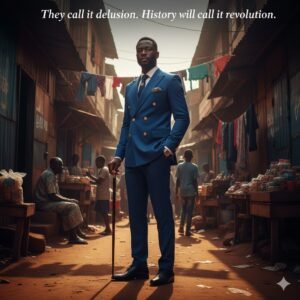

In Brazzaville and Kinshasa—where 70% of people survive on less than $2 a day—men spend three months’ salary on a single Versace suit. The West calls them delusional. History calls them revolutionaries. This is La Sape. And it’s the most brilliant hack of colonial power you’ve never studied.

The Revolution Will Be Accessorized

Picture this:

A dirt road in Brazzaville, Republic of Congo. Corrugated tin shacks patched with old campaign posters. Open sewers running between houses where whole families sleep three to a bed. Children barefoot in the dust, playing with bottle caps because real toys cost more than dinner. Average monthly income? $200 USD if you’re lucky. Most people aren’t.

Now.

Watch a man walk down that exact same street.

$3,000 Armani suit, cut so sharp you could shave with the shoulder line. Italian crocodile leather shoes—$1,500, hand-stitched in Milan. Silk pocket square that cost more than his neighbor’s monthly rent, folded with surgical precision. Hand-carved walking stick. Bowler hat tilted at a precise 15-degree angle, because angles matter when you’re making a statement.

He’s not lost. Not confused. Not having a breakdown.

He’s a sapeur. And he understands power better than most political scientists.

Look—Western media loves this story. They trot it out every few years when they need content that makes white liberals feel simultaneously fascinated and superior. The framing is always the same:

“Isn’t it tragic? These poor Africans, so desperate to imitate Western wealth, wasting precious resources on designer labels they can’t afford. If only someone could teach them financial literacy!”

But here’s the thing they never tell you:

La Sape—the Société des Ambianceurs et des Personnes Élégantes (Society of Ambiance-Makers and Elegant People)—wasn’t born in poverty seeking escape.

It was born in 1920s colonial resistance as a deliberate act of psychological warfare.

It exploded in the 1970s as direct defiance of dictatorship, when wearing a necktie could get you arrested.

And today? It continues as a radical reimagining of dignity, identity, and power in a world designed to strip all three away from Black bodies.

This has never been about clothes.

Wait—let me say that again for the people in the back:

This. Has. Never. Been. About. Clothes.

This is about what happens when colonized people weaponize the colonizer’s own symbols against him. This is about turning fashion into a theater of war. This is about reclaiming your humanity when every system around you is designed to deny you have any.

Real talk? The sapeurs figured out something in 1922 that we’re still trying to teach people in 2026:

The master’s tools can absolutely dismantle the master’s house—if you know how to reprogram them.

Let me tell you the real story.

The Origin: Stealing Dignity One Suit at a Time

Year: 1922.

Place: Brazzaville, capital of French Equatorial Africa (now Republic of Congo).

Scene: French colonial masters strutting around in expensive suits, top hats, walking sticks—the whole peacock performance of European “civilization.”

The message wasn’t subtle: We are elegant. We are refined. We are superior. You are savages who need civilizing.

Young Congolese men—houseboys, clerks, servants—watch this performance daily. They’re paid pennies. Often not even pennies—secondhand clothes instead of wages. Cast-off rags the colonizers wouldn’t be caught dead wearing themselves, offered as “payment” with the expectation of gratitude.

But here’s what the colonizers didn’t anticipate:

These young men looked at those expensive suits and said: “Nah. We want the real thing.”

Not the cast-offs. Not the knock-offs. The actual suits their masters wore. From the same tailors in Paris.

They used their connections—because houseboys traveled to France with their employers. They used their meager wages—saving for months, going hungry. They used their hustle—ways of acquiring things that don’t show up in the historical record but we all know existed.

And then? They wore those suits better than their colonizers ever could.

Historian Didier Gondola documents this moment beautifully. One French colonist wrote letters back home, absolutely scandalized by her houseboys’ fashion sense. She complained that these men would go half-starved—literally choosing hunger over lesser clothing—then parade around Brazzaville in designer suits that cost more than she paid them in a year.

The audacity. The absolute nerve of these Africans, refusing to know their place.

See, the sapeurs weren’t just copying European fashion. They were hijacking the entire semiotic system.

Every impeccably tailored suit said: “You claim we’re uncivilized? Look at us. We speak your language of power more fluently than you do. We understand your codes so well we can deploy them better. And we’re using them to mock you to your face while you’re too dense to realize it.”

This was jujitsu. Cognitive warfare. The colonizers’ own symbols of superiority, turned into weapons and pointed right back at them.

The Political Weapon: When a Necktie Becomes Treason

Fast forward to the 1970s.

Both Congos have independence now. But freedom came with chaos, instability, and in Zaire (now Democratic Republic of Congo), a dictator who understood spectacle as well as any sapeur.

Mobutu Sese Seko seizes power in 1965. By the 1970s, he’s implementing “authenticité”—his campaign to purge all Western influence and return to “true African values.”

Cities get African names. Christian names? Banned. Everyone must take African names.

And the most important change for our story: European suits and ties are outlawed. Criminal offense. You can be arrested.

The official uniform becomes the abacost—from the French “à bas le costume” (“down with the suit”)—a Mao-style tunic worn without a tie. Mobutu rocks this look himself: leopard-skin hat, thick-framed glasses, abacost, carved walking stick.

Some historians frame Mobutu’s ban as anti-colonial resistance. On paper, it sounds revolutionary: Reject the colonizer’s clothing. Embrace African identity.

But the sapeurs saw through it.

They saw a dictator using “African authenticity” as convenient cover for totalitarian control. They saw forced uniformity disguised as cultural pride.

And sapeurs don’t do uniforms.

So they did what sapeurs always do: They turned fashion into open rebellion.

Every three-piece suit became civil disobedience. Every Windsor knot tied in defiance of Mobutu’s decree. Every pocket square perfectly folded became a middle finger to dictatorship.

Enter the godfather.

Papa Wemba: The Pope Who Made Style a Religion

Jules Shungu Wembadio Pene Kikumba.

You know him as Papa Wemba. “The King of Rumba Rock.” The most influential Congolese musician of his generation.

But Papa Wemba was more than a musician. He was “Le Pape de la Sape”—The Pope of La Sape. The spiritual leader of a movement that treated fashion like salvation and designer labels like saints’ names.

In the 1970s—right when Mobutu’s banning Western fashion—Papa Wemba responds by making designer suits the centerpiece of his entire aesthetic. His concerts aren’t just concerts. They’re fashion shows. His videos are haute couture catalogues set to Congolese rumba.

He sings about “la religion kitendi”—the religion of cloth. Listing designers like prayers: Yamamoto, Versace, Gaultier, Cavalli. In his song “Matebu,” he literally catalogs the labels he dreams of buying in Paris.

His fans didn’t just listen. They converted.

They saved for months to buy used pieces from Papa Wemba’s own closet. They traveled to Paris and Brussels specifically to acquire clothing. They formed a literal hierarchy: archbishops, priests, popes, and saints (the saints being designers, not people).

Papa Wemba understood something crucial:

In a dictatorship where you can’t speak freely, where protesting gets you disappeared, your body becomes the last territory you control.

Colonel Jagger—a legendary Kinshasa sapeur—said it perfectly:

“This is a world where you can’t go out and shout in the street, where you suffocate, because there is no room to breathe. We don’t get mixed up in politics. But there’s a space that a dictator like you cannot control, and that is our bodies.”

Every sapeur walking down the street in a suit and tie was committing an act of resistance. Every color-coordinated ensemble was a political statement. Every peacock strut was defiance made visible.

La Sape became joy as resistance. Elegance as rebellion. Beauty as warfare.

And joy, in a dictatorship, is revolutionary as hell.

The Code: Rules Are How You Make Chaos Into Culture

Here’s what Western observers miss: La Sape has a strict moral and behavioral code that’s as important—maybe more important—than the clothing itself.

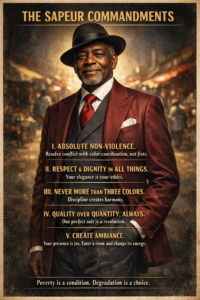

The Sapeur Commandments:

1. Absolute Non-Violence

Sapeurs are radical pacifists. In a region torn by civil war, sapeurs resolved conflicts through “fashion battles.” Competitive elegance. Strut-offs. Who can coordinate colors better. Not a single punch thrown.

2. Respect and Dignity in All Things

Sapeurs use refined language. Practice impeccable manners. Treat everyone with courtesy. The performance of sophistication isn’t superficial—it’s integral.

3. Never More Than Three Colors (Excluding White)

Maximum three colors in your outfit, not counting white. Why? Because discipline. Because intentionality. Because anyone can throw on expensive clothes. A sapeur curates, coordinates, creates visual harmony through constraint.

4. Quality Over Quantity Always

One perfect Yamamoto suit beats ten mediocre ones. Sapeurs share wardrobes. Swap pieces. The goal isn’t accumulation—it’s perfection in the moment.

5. Create Ambiance

“Ambianceur” doesn’t quite translate to English. It’s someone who creates atmosphere. Who brings energy. Who makes a room come alive just by entering it.

Sapeurs aren’t just well-dressed. They’re joy-makers in environments designed to crush joy.

They prove that poverty doesn’t have to mean degradation. That economic struggle doesn’t require surrendering your sense of self. That you can be broke and still magnificent.

The Afro-Futurist Reading: This Is Code-Switching as Liberation Technology

Now let’s talk about why this belongs in Afro-Futurist discourse.

Because what sapeurs have been doing since the 1920s is hacking the colonial operating system.

The colonizers created a visual language of power:

Expensive suits = civilization = superiority = right to rule

The equation was simple. Deliberate. Designed to be unreachable.

But the sapeurs did something brilliant. They reverse-engineered the code.

They learned the language fluently—more fluently than the colonizers expected. Then they deployed it for their own purposes, completely rewriting what the symbols meant.

Same suit. Different message.

When a colonizer wears it: “I am superior by nature, and these clothes prove it.”

When a sapeur wears it: “Your claims of superiority are bullshit, and I’m using your own symbols to prove it.”

This is the same technology enslaved people used when they created coded spirituals. Songs that sounded like religious hymns to overseers but gave escape routes to the people who needed to run. “Wade in the Water.” “Follow the Drinking Gourd.” Information hidden in plain sight.

This is the same technology Black musicians deployed when they took broken instruments and castoff rhythms and created jazz—turning the scraps of oppression into the most innovative art form America ever produced.

This is the same technology Black Wall Street used when they built a completely parallel economy inside a hostile system.

La Sape is cognitive warfare. Semiotic resistance. Taking the colonizer’s symbols and reprogramming them to transmit liberation.

When a sapeur walks down a dirt road in Brazzaville wearing $5,000 worth of designer fashion, he’s reprogramming the visual code that says poverty equals worthlessness.

He’s broadcasting: “The system says I should be invisible, degraded, broken. But I am magnificent. I am art. I am joy incarnate. Your economic violence cannot touch my dignity.”

This is Afro-Futurism in its purest form: Using the tools of the present to create the reality you want to exist in the future. Performing tomorrow into existence today.

The Complicated Truth: Every Paradise Has Receipts

But let’s be real about something the glossy photo books gloss over:

La Sape often comes at tremendous personal cost.

That $3,000 suit? For many sapeurs, it represents choosing clothing over food. Designer shoes over their children’s school fees. A silk tie over medicine when someone gets sick.

Some sapeurs openly admit they’ve financially ruined themselves pursuing the lifestyle. Marriages have collapsed. Kids went hungry so their father could look like a million dollars at a Saturday gathering.

The 2004 documentary The Importance of Being Elegant shows this. The “Archbishop”—a prominent Paris-based sapeur—eventually has a moment of recognition. Standing in his cramped apartment surrounded by suits worth more than his furniture, he says something that breaks your heart:

“All of this… it’s an illusion.”

So here’s the nuance Western observers rarely capture:

La Sape can be both revolutionary resistance AND destructive obsession. Both dignified self-assertion AND escapist fantasy. Both liberation strategy AND poverty trap.

The Afro-Futurist perspective doesn’t require us to romanticize everything. It requires us to see complexity without flinching.

Yes, La Sape is resistance. Yes, it’s psychological warfare against systems designed to degrade Black dignity.

And yes, individual sapeurs sometimes harm themselves and their families in pursuit of it.

The question isn’t whether La Sape is “good” or “bad.”

The question is: What does it tell us about what people need to survive in systems designed to destroy them?

The Women: Sapeuses Hijack the Hijack

For most of La Sape’s history, it was male-dominated. Exclusively so in Brazzaville—for 90 years, women were shut out completely.

But revolutions have a way of eating themselves. And the tool that disrupts one hierarchy can be used to disrupt the next.

In Kinshasa in the 1970s, a few women became sapeuses. Not to join the men. To challenge them. And more importantly, to challenge Mobutu, who was using “authentic African masculinity” to justify increasingly oppressive policies toward women.

These early sapeuses wore three-piece suits. Smoked pipes. Carried walking sticks. Adopted the full male sapeur aesthetic—not as costume, but as claim.

In Brazzaville, the movement remained closed to women until 2010, when the sapeur association finally launched recruitment for women.

Now? Sapeuses are rewriting everything.

They’re challenging both colonialism and patriarchy. Both the white supremacy embedded in fashion’s history and the male supremacy embedded in La Sape’s tradition.

One sapeuse said it perfectly: “People had reservations. They said we looked like lesbians. But I didn’t care. When I put on this suit, I feel powerful.”

Powerful. Not pretty. Not acceptable. Powerful.

The sapeuses understand: La Sape’s revolutionary potential comes from disrupting power hierarchies. All of them.

The colonizers used fashion to claim superiority over Africans.

Sapeurs used fashion to disrupt that hierarchy.

Now sapeuses are using fashion to disrupt gender hierarchies within their own communities.

It’s hacks all the way down.

The Ancestor Question: What Would They Build If They Had the Full Toolkit?

The sapeurs of the 1920s took the colonizer’s fashion and weaponized it.

The sapeurs of the 1970s turned Mobutu’s fashion ban into fuel for rebellion.

The sapeuses of the 2010s took a male-dominated movement and used it to challenge patriarchy.

Each generation remixed the technology for new battles.

So here’s the question: What would 21st-century sapeurs build if they had access to the full toolkit of liberation technology?

Imagine:

Congolese Luxury Brands Competing Globally

Not just buying Versace—creating the next Versace. Kinshasa becomes a fashion capital recognized on the same level as Paris, Milan, New York. La Sape Maison. Papa Wemba Couture. Brazzaville Atelier. The wealth stays in the community. The IP stays in Black hands.

Design Schools and Apprenticeship Programs

What if we built institutions in Kinshasa and Brazzaville that trained the next generation? Not just in fashion—in the philosophy of La Sape. The moral code. The resistance history. “Cognitive Warfare Through Fashion: How Visual Language Disrupts Power” as curriculum.

Blockchain-Based Sapeur Economy

NFTs of legendary outfits—digital artifacts of Papa Wemba’s most iconic looks, with proceeds going to his family and the community. DAO governance where sapeurs worldwide vote on collective resources. “SapeCoins” that reward cultural preservation. Smart contracts ensuring when Western brands use sapeur aesthetics, royalties automatically flow back to Congo.

AR/VR Experiences That Control the Narrative

Tired of Western documentaries telling our story wrong? Create immersive experiences where people worldwide can step into 1920s Brazzaville, walk through Papa Wemba’s closet in interactive 3D, participate in virtual fashion battles. Museum exhibitions that we own, control, and profit from.

Global Network of Sapeur-Owned Spaces

Physical locations in major cities—Paris, New York, Johannesburg, Lagos, Kinshasa, Brazzaville—that function as retail spaces for Congo-made luxury fashion, cultural centers teaching La Sape history, event venues for fashion battles, incubators for young designers.

Black Wall Street, but for fashion. Distributed globally. Owned collectively.

This isn’t fantasy.

This is asking: What’s the next evolution of a movement that’s survived 100+ years by constantly adapting?

Because La Sape has always been about more than the present moment. It’s always been about performing the future into existence.

The tools are different now. The mission remains the same:

Build systems that outlast you. Create infrastructure that multiplies throughout your community. Architect a future where Black excellence isn’t just celebrated—it’s economically sustained by structures we own and control.

The Lesson: Dignity Is Something You Perform Into Being

Western observers will never understand La Sape if they keep framing it as “poor people making bad financial decisions about clothes.”

Because that framing reveals their whole worldview: They think dignity is something you purchase with economic success. They think worth is determined by your bank account. They think poverty makes you less human.

Sapeurs know different.

Dignity isn’t something you buy. It’s something you perform into existence, day after day, regardless of material conditions.

La Sape is what happens when:

- You can’t afford therapy but you can afford a suit

- You can’t overthrow the government but you can overthrow the dress code

- You can’t change your material conditions but you can change the meaning attached to those conditions

- You realize the colonizer’s power comes from controlling symbols, and symbols can be hacked

Sometimes the most radical thing you can do in a world designed to degrade you is simply refuse to look degraded.

That’s not shallow. That’s not materialistic.

That IS the resistance.

The sapeurs of Congo walk through poverty looking like they own the streets. And in doing so, they’re doing what Afro-Futurism always does:

Creating the future through performance. Embodying the world they want to exist.

They’re saying:

Yes, we live in corrugated shacks with dirt floors.

Yes, the average income is $200/month.

Yes, colonialism destroyed our economies and dictators looted what was left.

And we are still magnificent.

And our dignity is non-negotiable.

And we will dress like the kings we know we are, even if the kingdom is dust and dreams.

That’s not delusion. That’s not waste.

That’s psychological warfare.

That’s maintaining your humanity in a system designed to strip it.

That’s building tomorrow while surviving today.

The sapeurs are time travelers, see. They dress like they’re already living in the liberated future where Black people own the means of production, control the cultural narrative, and walk through the world with the dignity that should have always been ours.

And by performing that future into existence—day after day, suit after impeccable suit, strut after unbowed strut—they make it a little more real.

That $3,000 suit isn’t a purchase.

It’s a weapon.

A tool of cognitive warfare in a century-long resistance movement that’s still teaching us how to hack power, disrupt hierarchies, and build the future we deserve.

The revolution will be accessorized.

And it will be magnificent.

Related Articles (Internal Linking Opportunities):

- Black Wall Street: The Blueprint for Economic Sovereignty

- The Underground Railroad as Decentralized Network

- From Jazz to Hip-Hop: How Black Culture Weaponizes Art

- Blockchain and Black Economic Liberation

Sources & Citations:

- Gondola, Didier Ch. (1999). “La Sape Exposed!: High Fashion among Lower-Class Congolese”

- Ayimpam, Sylvie. (2025). “The Black Dandy: Congo’s Stylish Sapeur Movement”

- Tamagni, Daniele. (2009). Gentlemen of Bacongo

- Amponsah, G. & Spender, C. (Directors). (2004). The Importance of Being Elegant [Documentary]

- Wrong, Michela. (1999). “A Question of Style”

- Zaidi, Tariq. (2020). Sapeurs: Ladies and Gentlemen of the Congo